Ben Plays: Quantum Break

When time comes undone, what’s done is done. Unless it wasn’t really done.

Speaking of time travel - and trust me, we are - it’s hard to believe Remedy Entertainment’s Quantum Break was released way back in 2016, just a month before, in the game, a ‘Fracture’ is set to effectively end the world, or at least humanity, by halting the progress of time completely. This is the conceit behind the blockbuster title, which seeks to blur the boundaries between video games and television by interjecting live action, roughly 20 minute long episodes that progress the story and adapt to the decisions you’ve made in game. In this regard especially, despite its ambitions, and even though it looks good for its age, I’m not sure you could argue it was ahead of its time: this TV-gaming blend hasn’t yet caught on. Thank God. But we’ll come to that.

As the player, you step into the collared leather jacket of Jack Joyce (played by Shawn Ashmore, of X-Men fame, though I preferred him in 2010’s Frozen) whose estranged, and just regular strange, brother William Joyce (Dominic Monaghan, aka Merry Brandybuck from The Lord of the Rings - after Lost he clearly found a taste for time travel) is an eccentric genius and possibly the only man who can save the world from time-tastrophe. Assisted by sassy seer, Beth Wilder (Remedy favourite, Courtney Hope, who also plays Jesse in Control), they set out to reverse or prevent the Fracture.

But wait - there’s an Evil Megacorp in the mix, Monarch Solutions, spearheaded by smooth supervillain Paul Serene (Aiden Gillen of The Wire, Game of Thrones) who grows increasingly less serene with every story beat, perhaps because he has agitators in his midst, like the enigmatic and always profoundly annoying, Martin Hatch (Lance Reddick, another alumni of The Wire, but perhaps best known to gamers as Sylens in Horizon Zero Dawn / Horizon Forbidden West, not a dissimilar character.) While Paul races to stop Jack and Will Joyce, Hatch is pursuing his own agenda - namely to scupper everyone else’s. There’s more to it, subplots involving craven geeks (actor Marshall Allman) and desperate husbands (actor Patrick Heusinger), but it all becomes a bit soap opera once you get into the weeds, so for simplicity I’ll spare you the details.

If you’re thinking, “Wow, that’s an all-star cast of the sort I assumed only David O. Russell could wrangle” - forgivably, after that Amsterdam trailer - you’re not too far wrong.

Quantum Break was directed by Mikael Kasurinen, but the casting of high profile actors is due to a misguided attempt to serialise its own story and release it in tandem, built into the game. These days it’s not surprising to find yourself manipulating celebrities in your gaming universe of choice. It’s been going on at least a decade, and now the tech is improving to near photorealism, enabling the actors involved to really flex some acting chops. To name just two recent (and major) examples, Death Stranding cast you as Norman Reedus and Cyberpunk 2077 cast you as Neo from the Matrix. I mean, Keanu Reeves. Even in 2016, character modelling was sufficient that the talent on display here are all instantly recognisable.

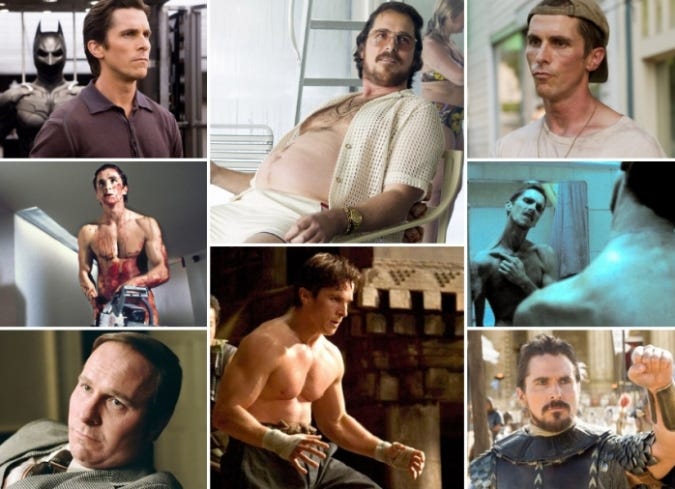

Listeners to the pod will know that by and large I’m not a big fan of this. It breaks immersion. There’s a neutrality to unknown gaming characters that operates in a similar way to characters in a book. Their outline is there, but you can shade in the colour and detail. They allow your imagination that bit more leeway. In some ways I find it peculiar that games are trying so hard to be cinematic (see my recent piece on this very subject), and limiting themselves to the same set of rules as the silverscreen. There’s a reason teams of people from make up artists to CGI animators are involved in mutating actors’ appearances - if they could change their physical appearance from film to film they would (Christian Bale almost manages it!)

Games have the power to introduce us to entirely novel characters every single time, but rather than lean into that, they’re spending big bucks on familiar faces. The cynic in me assumes this is for the same reason Hollywood studios are afraid to cast new people: audiences love a celebrity, and more eyeballs tuning in to see an A-lister’s performance means more dough 🫰, moolah 💰, scratch 🤑. Story, art and innovation is never the priority - it’s all about those dollar bills…

As mentioned, Quantum Break is interspersed with interludes of actual live action video, featuring the digital cast enacting the outcomes of all your decisions during gameplay. While there's nothing particularly wrong with these, they play out with that sort of hammy sense of escalated action and compressed drama more akin to fan made films than multi-million pound blockbuster titles. The content itself is vaguely reminiscent of Jonathan Nolan's Person of Interest: a convoluted sci-fi story complete with flashy, low budget, fun but implausible style action thriller set pieces. They're entertaining enough to keep you switched on for their runtime and do an effective job of humanising the key players, but instinctively, I wasn't a fan. When I sit to play a game, I want to play a game. If I wanted to watch bad TV, I'd watch it.

I had anticipated these sequences would be 'fill in the gaps' type cut scenes, much like regular video game cut scenes but acted rather than animated. In fact, it starts to feel like these are where the real jumps in story take place. So many of the key story developments are left to unfold in the live action episodes that it undermines the progress you feel you make in the gameplay. Not to mention, these sequences don't replace regular cut scenes, which still pepper the game throughout. As I wrote previously when discussing video game adaptations and their inadequacies, some silliness that makes gameplay more exciting or rewarding can be forgiven in games, but TV doesn't enjoy the same privileges, even when the actors look and sound (and are) the same. Quantum Break is often more TV than game.

All that said, there are elements of Quantum Break’s approach that work really well. For a start, it’s incredibly engaging, weaving retrospective voice-overs in the same stylish way Remedy pioneered with Max Payne. The visuals, the voice acting and acting in general, the sound effects and implementation of your time manipulation abilities - everything feels smooth and well choreographed. A bit too well choreographed if anything, because much like in The Order: 1886, a 2015 third person adventure game so desperate to be cinematic it surrendered nearly all free thinking gameplay to the cause, it holds your hand too tightly, as if afraid its clever time travel plot might unravel if you stray too far from the path destiny (and the writers) have laid out for you.

Banalogy time. To enjoy Quantum Break, you first need to accept you're not really going to play it in a conventional sense. Instead, you need to think of it more like reading a particularly immersive book, never straying from the words on the page, absorbing what's right in front of your nose, then turning the page for the next few lines of story. Just as you can't (coherently) read a book in any old order, and your experience of it will not drastically differ from the next reader's (this banalogy is already starting to break down), neither can you forge your own path through Quantum Break. It is a carefully curated experience, right down to which buttons to press and when. Tao mockingly called it ‘Quicktime Break’, a jab at its use of quicktime elements. While they're not quite as egregious as that suggests, the game is certainly riddled with controller prompts. You also never really get the sense you've discovered something for yourself because every interactable is highlighted at the press of a button in 'Time Vision', and every puzzle is slapped in front of you right next to its simplistic solution.

Fortunately, if you're not wedded to autonomous gameplay and you're happy to fairly passively consume an intriguing sci-fi story, it's still a gripping yarn. And that's not to say it doesn't try to convince you your play-through does have variety: it uses a device it calls a ‘Time Junction’ to give you a sense of control. This is a two pronged fork in the narrative after each Act. Oh, yeah, I may have forgotten to mention: It’s not just the actors that emulate cinema. The story also unfolds in Acts. And Parts. And Junctions, apparently.

By way of example, the first such choice is whether Paul Serene and Monarch Solutions should eliminate all witnesses to the Fracture and the immediate events leading up to it - these witnesses are mostly students at a university protesting about the demolition of a heritage building (which alone may predispose you one way or another) - or whether they should push for a PR campaign, threatening these witnesses, coercing them into spinning Monarch’s angle and thereby advancing their agenda. I didn't see this choice, or any of the Time Junctions, as a decision between right and wrong, so much as two different approaches to the campaign, rather like in Deus Ex deciding whether to tackle a squad of heavily armed enemies head on, or to use a stealthy vent and go around them. These options ask not which is the correct answer, but which answer speaks to the kind of gamer you are. Of course, you know you can always play again to choose the other fork, so in either case the outcome doesn't feel too weighty. While I’m not inclined to replay right away, knowing that there are alternative versions of all the episodes I watched (and potentially played), does make me at least open to the idea.

The story itself is quite clever, though not without problems, and its characters are satisfying shades of grey. Morally, I mean. There’s nothing erotic going on. For example, arch villain Serene is made sympathetic, suffering as he does with an incurable illness, and with an ultimately benevolent ambition of prolonging humanity's survival. His methods might be ruthless, but maybe the ends justify the means. (No-one told Aidan Gillen though, who delivers every line with the unctuous drawl of an unrepentant, self-satisfied megalomaniac. A strong performance, if not particularly fair to the written character.) Even your character, Jack Joyce, dedicates himself to saving the world right up until he’s confronted with ulterior motives - saving a love interest, revenge for the loss of a loved one - and then he’s not quite so clearsighted. Meanwhile Monarch’s top security operative and executioner, Liam Neeson Burke, turns out to be a doting husband and father-to-be with a very particular set of skills.

Not all characters are given the luxury of nuance. There’s a security guy who enthuses, 'I'm really gonna enjoy killing your wife' and a scientist who quietly abandons his whole family in the night to save his own skin. These people don't feel plausible. That's not to say I don't believe malicious, sociopathic individuals exist. I'm just not convinced they all end up working for one organisation (although the UK government and Tory party is doing its best to dissuade me of that notion).

Due to its innate complexity though, there's more exposition in Quantum Break than a Christopher Nolan movie, delivered not just by the cast, whose ignorance on all things is an opportunity for other characters to fill them (and you) in on backstory, but in verbose emails at logged in computers (their op-sec sucks), waffling presenters on live TV feeds, inarticulate goons over radio chatter, and all that in addition to more conventional collectibles like schematics, posters, graffiti... the list goes on. In fact, there's so much exposition, most of the time it audibly and visually overlaps in a really distracting way. For instance, two characters are talking, but you want to open a door which interrupts them with a mini cut scene, then one of the NPCs wanders off demanding that you follow them, but you're still reading page one of an emailed novel from Carol in IT...

The only way to take it all in without endless interruption is to leave your character milling about waiting for each audio sequence to end, and ignoring the pleas of nearby NPCs exhorting you to get on with story progress while you click on every interactable in the environment. Some areas have more than others. In one scene, during a protracted Stutter - when time stops, freezing everything and everyone except you - there are two floors of office rooms to explore and it seems every single cubicle has at least one item that triggers a wall of text and lore to catch up on. Jack kept insisting the Stutter was going to collapse soon and I didn't have all day, but the devs didn't get the memo and had left so many memos for me to read I took me chances. Spoiler: I was fine.

Like with Control and the Uncharted games - even The Last of Us to some extent - the problem with focusing on narrative to the exclusion of real gameplay is that the player spends the game levelling up special abilities and unlocking new and improved skills, but there are precious few opportunities to actually use them. Once, after about 20 minutes of uneventful, room to room, story based interactions, finally a horde of enemies descended on me simultaneously in a garage, and I thought gleefully, ‘now we're talking’. I could slow time, pause it in localised zones, stacking bullets to riddle the enemy as soon as it resumed, sprint across huge distances in bullet-time, blink in and out of enemy vision while relocating with ‘Time Dodge’, and I was armed to the teeth. It felt like a recipe for fun. But three minutes later, after using maybe half of my talents and exerting very little effort, they were all dead and I was back on rails for another dry section. Where a hack and slash like Diablo or Darksiders (or Wolcen!) throws endless waves of enemies at you, giving you ample time to flex, Quantum Break rations encounters out as though giving blue M&Ms to children. Only the M&Ms at least give you a sugar rush.

Those who listen to the pod will know I'm not exactly a glutton for punishment, but that doesn't mean I don't relish a stimulating challenge. This game's 'normal' difficulty feels like 'God mode' or at least, 'very easy'. The various environmental hazards littered around for you to exploit to take down ‘Monarch Flunkies’ - as the game calls them - are entirely superfluous, because a few well placed shots down even elite opponents. My only deaths resulted from lack of clarity during the glitchy splintering visuals. There were a couple of moments this proved tiresome: when time freezes during Stutters it is usually in the middle of some dynamic explosion, and you navigate the objects being decimated as a visual distortion ripples through the surroundings. These objects are sometimes unstable, and flit between different positions. They can catch you unaware, particularly as the edge of their danger zone isn’t very well demarcated. Also, in the inevitable boss battle with Paul Serene, his attack isn’t so much an attack as a ballooning orb of death that corrupts your visuals. It’s a one hit kill. Once you’ve figured out the boundary, it’s trivially easy to avoid, but that boundary is obscure by design. More infuriating in this section is actually that the save point ahead of this boss fight is before a cut scene, so every retry, you’re forced to skip it and endure a loading screen. This shit has got to be trolling by the devs at this point…

All this leaves Quantum Break with a major flaw: it mostly asks the player to grind for all the wrong things, the unfun things. When the combat is limited, brief and unchallenging, the puzzles are basically non-existent, and the bulk of the work is running from Intel point to Narrative Object reading endless texts, what you end up with is pseudo-gameplay. The exciting story, vividly realised world and rich characters make it worth a run through, but it sadly feels so much less than the sum of its parts.

Further listening: